Precis Of 2020:

The Year 2020 has carried with it many unforeseen obstacles. Although scientists and physicians raced to make an antidote for the innovative coronavirus that threatens to devastate communities across the world, policymakers failed to deal with the global pandemic chaos that practically brought commercial life to a halt for months and years to come. For a developing nation like Pakistan, which is in a mountain of debt and already part of the IMF bailout program, the scenario posed an almost impossible challenge. In its second full year of governance, the PTI Government had its bags packed on combating the spread of the deadly virus, battling the country’s current account, the economy overall, and resolving the demands of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) to name a few, all while grappling with incredibly hostile resistance.[1]

Sugar & Wheat Inquiry Report:

Pakistanis were left chasing their tails as goods perceived to be staples wheat & sugar had apparently vanished from the markets or had been sold at extortionate prices since late last year. To make it worse, the government was as shocked as customers about what was actually going on. Earlier in the year, on the directions of Prime Minister Imran Khan, the government set up a commission to investigate price hikes and the scarcity of wheat and sugar.[1]

In April, many investigative findings were made public and left the ruling coalition in red because it included PTI’s Jahangir Tareen, a personal associate of the PM, and allied party leaders, Khusro Bakhtiar and Monis Elahi, among others. As per the reports, six major sugar mill groups acted as “cartels” and committed bribery while bad procurement resulted in a shortage in wheat. Shortly thereafter, Tareen, whose friendship with the prime minister seemed to have soured, fled the country for “medical treatment” However, he returned to Power in November and said that he would support the government in its attempts to manage the shortage of sugar and the increase in prices. In an attempt to monitor the situation, the government has recourse to rising imports and cracking down on hoarders to ensure the supply of goods on the market, ultimately leading to a decline in sugar prices. In December, the Prime Minister congratulated his team on the lowering of sugar prices through a multi-pronged approach. To date, however, no meaningful action has been taken against those listed in the investigative reports as having indulged in unethical business activities to benefit from shortages and price hikes[1].

12-Year High Expansion Record:

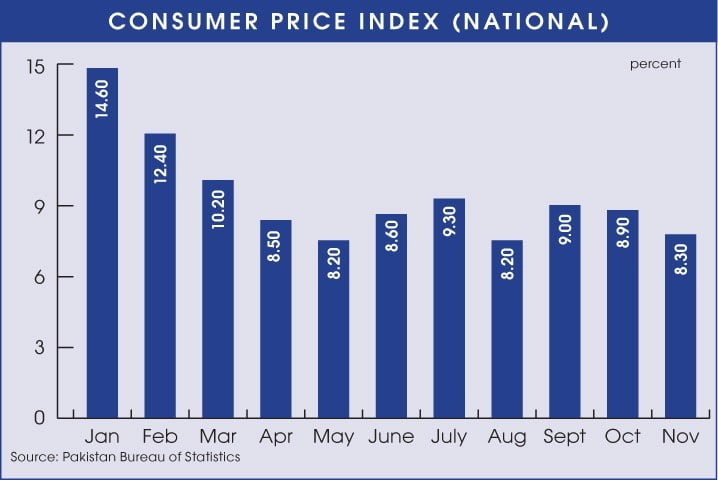

The scarcity of two critical goods had led their prices to skyrocket at the end of last year, and the pattern persisted into the new year, which started with a bang in far more aspects than one. The January inflation rate rose to 14.6pc, from 12.6pc in the previous month to the fastest amount in 12 years. Data released by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics showed that higher food prices, especially those of essential commodities, were the biggest driver of consumer prices. Before the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, the State Bank of Pakistan had held its main policy rate at 13.25pc for several months in an attempt to combat inflation. However, between March and June, the federal reserve reduced the policy rate in the double digits to 7pc in less the 100 days[1].

The switch to lower prices was triggered by the IMF’s prediction that Pakistan’s economy would shrink by 1.5 pc during the FY20 when the pandemic struck the global economy. As a lower interest rate stimulates investment, the change was aimed at mitigating economic harm[1].

Following the high in January, the downturn in economic activity triggered by the lockdown helped to alleviate inflation in the coming months, and the government’s attempts to bring down the prices of wheat and sugar have paid some dividends. By November, total inflation had decreased to 8.3pc, but food inflation, which remains in double digits, had risen in the same month. Food costs have stayed high this year due to a variety of reasons, including the coronavirus pandemic. In December, the UN Food Agency said that global food product prices increased dramatically to their highest level in almost six years, attributing an uptick in adverse weather conditions. As for Pakistan, the prices of imported food products tomatoes, onions, chicken, eggs, sugar, and wheat have risen steadily over the last few months. Egg prices increased across the country in 2020 to Rs200-240 per dozen[1].

Prime Minister Appeal for Debt Relief:

Soon after the disease outbreak struck, the Prime Minister called for a global debt reduction program for developed countries to help resolve the economic implications of Covid-19. In April, Prime Minister Imran appealed to the representatives of rich countries, the UN Secretary-General and the heads of financial institutions to grant developed nations debt forgiveness so that they could help fight the virus while also tackling other economic challenges. The Prime Minister’s drive, called ‘Appeal for an International Debt Reduction Plan,’ was followed by comprehensive diplomatic outreach from the foreign ministry. Following the Prime Minister’s appeal, the G20 declared that Pakistan had been included in a community of 72 countries eligible for debt relief on both principal and interest payments to connections creditors[1].

The Paris Club decided in June to postpone debt service contributions from Pakistan, Chad, Ethiopia, and the Republic of Congo. Pakistan secured $1.7 billion in debt reduction arrangements with 19 bilateral lenders in December. Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi named the movement the related to the large effort that Prime Minister Imran spearheaded during his tenure as Prime Minister, saying that the program had helped the developed world in a period of emergencies[1].

Economy Slims First Time in Decades:

Pakistan’s economy experienced a significant setback, with all primary industries struggling to reach estimates as a result of the coronavirus epidemic, resulting in a negative 0.38% economic growth rate in the fiscal year 2019-20. This was the first time the economy had shrunk since 1968. The services sector has been a big factor for economic growth in the country for a number of years, but there has been a rare contraction of 0.59 pc for FY2019-20. The primary cause for the crash, as predicted, was the effects of Covid-19 and the downturn in service delivery in major sectors. However, the agricultural sector had a marginal improvement of 2.67 pc, while manufacturing production had declined by 2.64 pc. The Government had estimated 3.5pc production in agriculture, 2.3pc in making, and 4.8pc in projects for the year 2019-20[1].

The only silver lining in these findings, though, was that the contraction was not as extreme as expected by the World Bank and the IMF. As it turned out, Pakistan was on target for a v-shaped rebound starting in the second half of 2020 thanks to a phenomenal performance in coping with the first wave of the virus and the steady opening up of the economy. In November, intending to raise the macros, the State Bank revised upwards its forecast of economic growth for the current fiscal year (2020-21) to 2.5 pc compared to the 0.4 pc contraction seen last year. The current growth forecast was marginally higher than the government target of 2.1pc and the bank’s own earlier estimate of a maximum rise of 2pc in GDP. The growth forecast was based on forecasts of stable agricultural efficiency, a rebound in the services sector, and a moderate rise in industrial production[1].

Oil Crisis:

In June of this year, petrol abruptly vanished from the markets, resulting in one of the worst fuel shortages in the world in recent times. The limits during the first week of June, at a time when the government had lowered fuel prices in line with global prices, which had slumped on the back of low demand due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The drive to cut costs locally resulted in an effort by the oil industry to stop inventory losses, which ultimately resulted in a crisis. Then a public spar between the government and the oil marketing companies (OMCs) began, each of whom blamed the other for the incompetence that brought the country to this situation. Although the players involved in the supply chain were at odds, the customer struggled and often had to pay double the price to get the goods[1].

The supply chain disturbance occurred worldwide and impacted all major cities and towns in Punjab, Baluchistan, Azad Jammu, and Kashmir, and Gilgit-Baltistan. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa officially said that its 77 gas stations had absolutely dried up. The situation started to normalize after the lockdowns were lifted in July and traffic from international borders began to pass, but most notably after the government reversed its earlier position on price cuts and declared a record rise in the prices of petroleum products. Earlier this month, a scathing report by the Audit Committee set up on the orders of the Prime Minister found that there were issues at every stage of the supplied chin that caused the crisis. Throwing serious accusations across the oil distribution chain, from decision-makers to regulators and industry operators to retail outlets, the 15-member crisis commission proposed departmental action against the top leadership of the oil division, the dismantling of Ogra, and the suspension of Byco’s refining and oil marketing activities. Action on these recommendations is about to be taken by the Commission[1].

Good but not Good Enough, FATF Review:

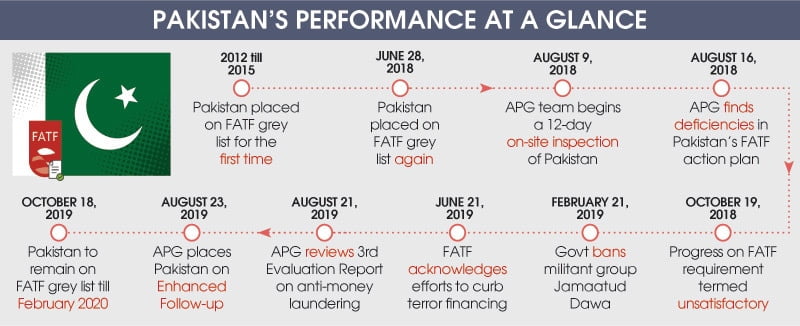

For the past year, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and the risk of being on the gray list have once again been the government’s top priority. In October 2019, the FATF firmly urged Pakistan to complete its full action plan quickly by February 2020 before the nation remains on the gray list. However, in February, the FATF issued Pakistan a six-month extension to resolve the remaining points in its action plan. But Pakistan’s case was not taken up at the June conference, and it was reported that the nation would stay on the gray list until October. A concrete and much-awaited announcement eventually arrived in October after the FATF agreed to give Pakistan a four month extension to fulfill the remaining six of the 27 goals of the Action Plan [1].

Though Pakistan remains on the so-called gray list of the FATF, the government has said that the blacklisting of the country is now “from off board” [1].

Current Account Unprecedented 5-month Surplus Streak:

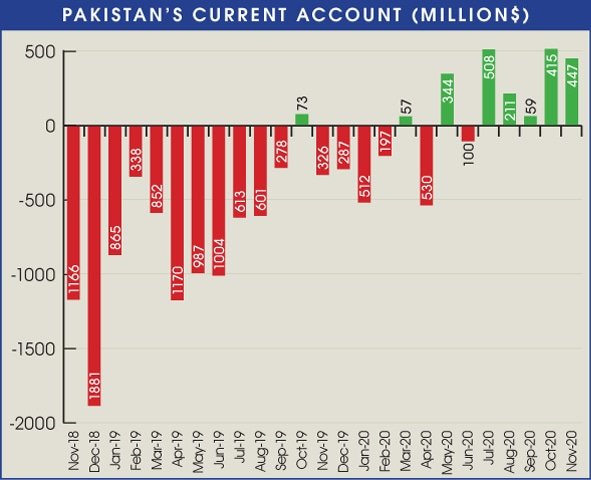

Pakistan’s money market, the status of which has lately become a favored measure for government officials to use when hitting their opponents back, has also seen some change. Pakistan’s fiscal deficit decreased by 78pc in the FY2019-2020 period, according to data from the State Bank of Pakistan. The current account deficit reduced to $2,966 billion in FY20 compared to $13,434 billion in the previous fiscal year. Since July, there has been a surplus in the current account for five straight months. In October, the Prime Minister said that the nation was “headed in the right direction finally” as the current account experienced a historic surplus of $792 million in the first quarter of the current fiscal year. The upward trajectory accelerated as the current account experienced a surplus of $447 million for the fifth straight month in November compared to a shortfall of $326 million for the same duration last year[1].

As per the banking system, the current account has remained in surplus across the current financial year due to an improving trade balance and a sustained growth in remittances. In addition to strengthening the payload, the “restoration” of the current account has also boosted the SBP’s foreign exchange reserves to their highest level in three years[1].

A New Airline During a Pandemic:

Although 2020 brings with it some absolutely grim moments, there have still been some optimistic changes. One such moment was the launch of Air Sial, a private airline spearheaded by Sialkot’s business class, in the middle of a pandemic. Although the three operating airlines of the country have taken cost-cutting steps against the backdrop of the crisis that the global aviation industry has been facing since the coronavirus outbreak, Air Sial’s decision to join the already crowded market is seen as a daring move that could give rivals a tough time but will help the public. The inauguration of the new airline was followed in the same year by a government investigation into Pakistan International Airlines after a horrific crash that took the lives of 97 citizens showing that many pilots operating for the national flag carrier did not have the required qualifications[1].

Air Sial commenced trading on Dec 25 with its first flight from Islamabad to Karachi. The airline announced that it would initially fly on domestic routes to and from Karachi, Islamabad, Lahore, Peshawar, and Sialkot. It still plans to travel to international destinations, though.

Other innovations worthy of note include British Airways, which operates direct flights from Lahore to London, and Virgin Atlantic, which operates direct flights to Pakistan[1].

A Volatile Year for the Rupee:

Like other elements of the economy, the coronavirus pandemic was instrumental in deciding the currency exchange market course. At the beginning of the year, just before the onset of the pandemic, the US dollar was trading about Rs154.64 on Jan 2, according to data published by the State Bank. As a result of the outbreak of the virus and the subsequent lockdown on March 21, the dollar started to increase as pressure increased on the rupee after the pandemic did significant harm to foreign trade with the region, which witnessed an early negative effect on orders. With exports down sharply, demand for the dollar has started to increase. By 8 April, the rupee had felled to a record low at the time, Rs167.90, in interbank trade. The rupee slide was intensified by the lowering of interest rates by the central bank, which makes domestic treasury bills less enticing to foreigners, forcing them to disinvest their holdings[1].

The rupee saw the rock bottom of the year on 26 August, since it was traded to an all low of Rs168.43 a fall of around 9pc so far. But since then, after the nation quickly tackled the first surge of viruses, the shutdowns relaxed and the market operation picked up, and so did the rupee. The spike in remittances and the strengthened trade balance (low imports and rising exports) ensured that the rupia began a three-month rally in August, which lasted until the end of November when it hit almost Rs10 to Rs158.49, just Rs3.85 or 2.4pc lower than when it started the year (Rs154.64). As of December 28, the rupiah traded at Rs160.3 against the dollar according to SBP data i.e. a decrease of Rs5.66 or 3.66pc year-to-date[1].

2 Pakistan Firms on Forbes list:

The success that deserves inclusion in this category is the inclusion of two local businesses on one of Forbes’ most famous lists for 2020. In December, information technology company Systems Limited Pakistan (SLP) and garment and textile giant Feroze1888 Mills made Pakistan proud of the list of Forbes ‘Asia’s Best Under A Billion 2020. ‘The annual list honors 200 top-performing small and medium-sized businesses in the Asia-Pacific region with revenues of less than $1 billion. The accomplishment was also hailed by the PM’s aide, Abdul Razak Dawood, who expressed trust that the acknowledgment of these companies would “provide an incentive for others to produce good laurels”[1].

Reference:

Source: Published in Dawn

https://www.dawn.com/news/1594880 [1]